Making of a Painting V: The Dormition-Assumption

Introduction

When we were commissioned to create a depiction of Christ carrying his mother’s body to Paradise, we recognized it as an exciting opportunity to build a bridge between the iconographic traditions of East and West.

The Literary Tradition

Scattered references to the death of the Virgin Mary are found in various pseudepigraphical sources in the early centuries of Christianity, but starting in the late 400s A.D. the outlines of an accepted story began to take shape in the mainstream literary tradition. According to this narrative, Mary died some years after Pentecost. Three days later, her body mysteriously vanished from the tomb (replaced in some accounts by fragrant flowers), and it was understood that her physical remains had been reunited with her soul in Paradise.

The Artistic Tradition

Dormition

Artistic representations of this story in the Eastern churches have historically focused on Mary’s peaceful death and are therefore referred to as the “Dormition” icon, after the Latin term for “falling asleep.” In the standard rendition, Mary’s body is laid on a bier, while her Son carries her soul—depicted as a newborn infant wrapped in swaddling clothes—to Heaven.

Mt. Sinai, Dormition of the Theotokos (ca. 1250)

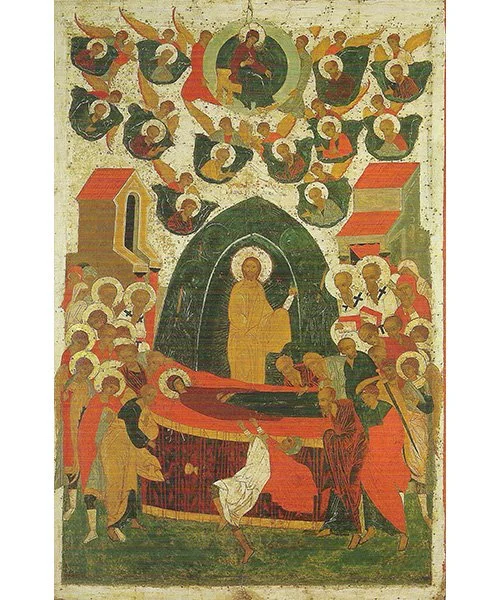

Russian, Dormition of the Theotokos (ca. 1300)

Theophanes, Dormition of the Theotokos (1392)

The portrayal of Mary’s soul as a child highlights her innocence. The motif is also an intentional role-reversal with respect to the iconography of the Nativity: just as Mary ushered her infant Son into the phenomenal world when he was born in Bethlehem, so now Christ ushers his Mother into a new realm as she is reborn into eternal life.

Although the Dormition theme is generally associated with Eastern Christian art, it also appears in the Western canon prior to about 1500 A.D., as can be seen in the following Medieval and early Renaissance examples.

Jacopo Torriti, Dormition of the Virgin (1296)

Fra Angelico, Dormition and Assumption of the Virgin (detail, ca. 1430)

Assumption

Starting in the sixteenth century, depictions of the end of Mary’s life in the West have generally focused on the translation to Paradise not only of her soul but also of her body. The Blessed Virgin is often shown rising from a tomb or sarcophagus, implying an initial death/dormition. In contrast to the Eastern tradition, however, she nearly always appears revivified—already in a resurrected/glorified state—as the translation takes place. A company of angels is often present to escort her to Paradise, there to be reunited with her Son (who may or not be depicted).

Nicolas Poussin, Assumption (ca. 1631)

Francesco Solimena, Capua Assumption (ca. 1725)

Corrado Giaquinto, Assumption (ca. 1740)

Again, although the Assumption motif is generally associated with Western Christian art, it is occasionally seen in Eastern works, though only as an elaboration on the traditional Dormition icon.

Russian, Dormition and Assumption of the Virgin (ca. 1525)

Elias Moskos, Dormition and Assumption of the Virgin (1679)

Enter GFA

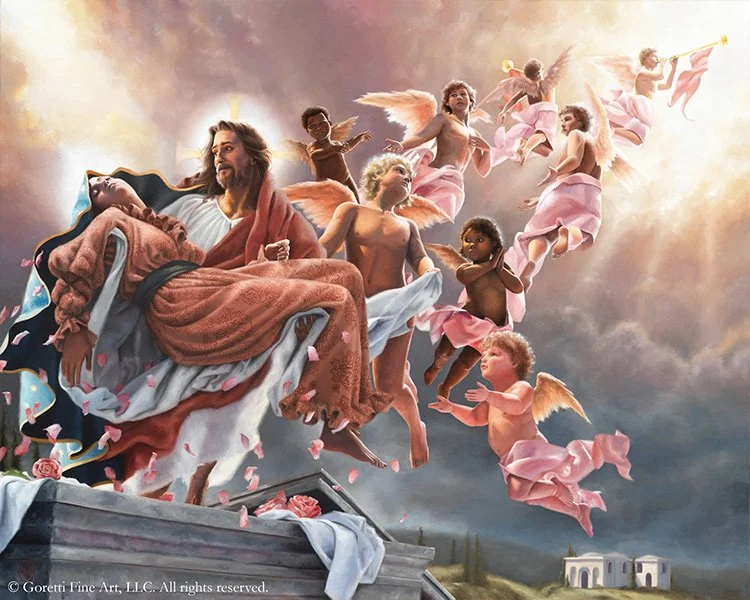

It was with this historical context in mind that we approached the commission to create a novel depiction of Christ assuming his mother’s body to Heaven. The request suggested a meeting of the major motifs of Eastern and Western interpretations of the subject and thus presented the exciting challenge of harmonizing these disparate tradition-streams in a manner that respected each. The final 24x30” oil painting that resulted from this effort, informed by both our research and several helpful rounds of input from the client, can be seen below.

The Dormition-Assumption (2025)

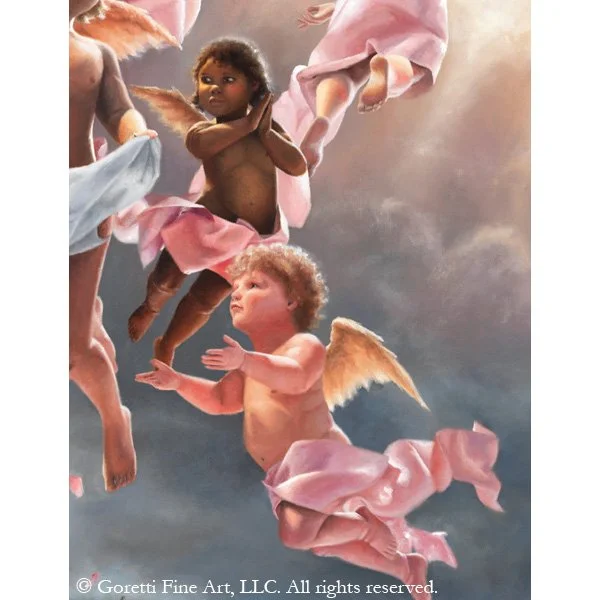

Like the classic Western renditions, the composition we developed involves the Virgin’s bodily assumption from the tomb amid a shower of rose petals and the jubilation of an angelic escort.

The painting’s Illusionistic style, of course, is also solidly Western.

In keeping with the Eastern tradition, however, Mary’s body remains in the repose of death, not yet reunited with her soul. Similarly, in a nod to the Dormition icon, Christ cradles his mother in a visually evocative role-reversal. This time, instead of paralleling the Nativity, the scene calls to mind the Deposition: just as Mary tended to her Son’s body following his death on Calvary, so now Christ returns the favor, lovingly tending to his mother’s body following her passing and preparing it, not for a tomb, but for Heavenly glory.

We made this connection to the Deposition explicit by modeling Mary’s supple pose on that of Christ in Michelangelo’s iconic Pietà.

Compare the pose of Christ in Michelangelo’s Pietà (1499) with that of Mary in The Dormition-Assumption.

Although this creative union of Eastern and Western motifs resulted in an innovative depiction that differs in key respects from traditional portrayals, it is not without precedent. Indeed, key elements are anticipated by examples from art history, particularly in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, before the Assumption motif became standardized in the West.

For instance, the image of Christ descending to claim his mother’s deceased body is on full display in these powerful fifteenth-century depictions by Taddeo di Bartolo and Hugo van der Goes, respectively.

Taddeo di Bartolo, Assumption of the Virgin (ca. 1410)

Hugo van der Goes, Death of the Virgin (ca. 1475)

Similarly, the following fourteenth-century renditions show Christ—either personally or through the mediation of an angel—returning for his mother’s physical remains after having already taken her soul (depicted as a young girl in the upper register on the left and in the lower register on the right) to Paradise.

Younger Master of the Gradual, Dormition of the Virgin (ca. 1335)

Ugolino di Prete Ilario, Dormition and Assumption of the Virgin (ca. 1370)

Other Features

Other notable elements of our composition include Mary’s physical appearance and clothing. At the request of the client, we depicted her as the Virgin of Guadalupe—an idealized young Mesoamerican woman wearing a starry mantle, a pink dress bearing a distinctive floral print, and a black girdle.

Although most early sources place Mary’s death in Jerusalem, a minority view connects the Dormition and Assumption with Ephesus, since John the Evangelist (who took her into his care following the Crucifixion—see Jn 19:27) is traditionally associated with that city. At the request of the client, therefore, we included in the background of the painting a depiction of the so-called “House of Ephesus,” an archaeological structure on Mt. Koressos, Turkey, which a tradition dating to the nineteenth century holds to be her final dwelling place.

Conclusion

Although at first glance The Dormition-Assumption appears highly original, it is steeped in the literary, theological, and artistic traditions relating to the Blessed Virgin Mary. It combines motifs in creative ways but, like all good sacred art, is informed by the Church’s iconography as it has developed through the centuries. The result is a painting that we hope will deepen our appreciation for the inexhaustible mystery of the Assumption and help us contemplate the power of God’s grace to transfigure all things, even death.

Further Reading