Angels in Art (4 of 4): Compositional Devices

Introduction

In the previous post, we analyzed the narrative roles that angels play in the stories that works of art are telling. In this final installment of our Angels in Art series, we turn our attention to the ways that angels can serve as artistic devices contributing to a painting’s design and aesthetic force.

Compositional Devices

Inviting the Viewer to Participate

First, angels can provide a useful means of inviting and guiding the viewer’s participation in a scene. For example, in the work below by Sebastiano Conca, note how the angel in the lower left engages the viewer by direct eye contact and, with a prominent gesture, draws his or her attention to the painting’s main figures.

Sebastiano Conca, Madonna of the Apocalypse (ca. 1730)

Drawing Out Emotional Content

Even though angels are not subject to emotion, anthropomorphizing them in this way can be a useful technique to establish a mood and/or emphasize the affective content of a scene.

Giotto, Lamentation of Christ (ca. 1310)

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, Pietà (ca. 1667)

It’s perhaps no surprise that we see this in the melodramatic Baroque era…

Anthony van Dyck, Lamentation over the Dead Christ (ca. 1635)

…or the highly sentimental nineteenth century…

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Pietà (1876)

…but it is common in the Eastern tradition as well.

St. Catherine’s Monastery (Sinai), Crucifixion (detail, ca. 1260)

Grief is not the only emotion highlighted in this way. In Sandro Botticelli’s famous Mystical Nativity, angels are dancing and embracing for joy.

Sandro Botticelli, Mystical Nativity (1501)

Highlighting Spiritual Significance

Angels also provide an opportunity to highlight the spiritual significance of what might otherwise be mistaken for a mundane, earthly scene. For example, when Jesus conferred the keys on Peter, it wasn’t because Judas had changed the lock on the Apostolic money bag. Rather, this was a highly metaphorical, spiritually charged gesture, and the angels filling the celestial register in Giovanni Battista Pittoni’s depiction below are designed to remind us of that fact.

Giovanni Battista Pittoni, Keys of the Kingdom (ca. 1740)

Similarly, in The Last Communion of St. Jerome, the cherubs visually cue us in to the fact that the meaning of the scene transcends the physical nourishment that the old man is deriving from the wafer of bread.

Domenichino, Last Communion of St. Jerome (1614)

This motif is especially prevalent in Christmas art—it tells us that something of tremendous spiritual importance is happening and that this is no ordinary human birth.

Anton Raphael Mengs, Adoration of the Shepherds (ca. 1770)

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre, Nativity (ca. 1775)

Foreshadowing

Artists often use angels as a device for introducing foreshadowing. In these scenes, the future martyrdom of the respective saints is foreshadowed by the angels carrying the palm branch of blessedness, the crown of martyrdom, and, in the case of St. Andrew, the instrument of execution.

Carlo Cignani, Condemnation of St. Andrew (1665)

Francesco Solimena, St. Januarius in Prison (ca. 1700)

Sebastiano Ricci, Communion and Martyrdom of St. Lucy (1730)

The Heavenly glory that awaits these saints as they are being killed is likewise conveyed by the symbol-bearing angels.

Federico Barocci, Martyrdom of St. Vitalis (1583)

Giambettino Cignaroli, Martyrdom of St. Lawrence (ca. 1755)

Introducing Signs and Symbols

The previous section serves to highlight a more general theme, namely that angels are useful artistic devices for introducing signs and symbols into religious paintings.

For example, one of St. Anthony’s attributes is the lily—the way we can tell that we’re looking at a depiction of Anthony of Padua and not of some other Franciscan friar is often from the lily in his hand. But, in the painting below, St. Anthony’s hands are full: there’s no room for both the Christ Child and a lily. So an angel is helpfully presenting the flower, which might otherwise have to be left out of the composition.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, St. Anthony of Padua with the Christ Child (ca. 1675)

Below, angels are holding St. Augustine’s crozier, the sign of his pastoral authority, so his hands are free for the dramatic gestures, while, on the right, an angel presents the metaphorical “cup” referenced by Jesus during the Agony in the Garden.

Claudio Coello, Triumph of St. Augustine (1664)

Corrado Giaquinto, Agony in the Garden (ca. 1754)

In Sebastiano Conca’s beautiful ceiling fresco, an obliging angel even shoulders a whole pipe organ so that we can identify the virgin receiving her martyr’s crown as St. Cecilia.

Sebastiano Conca, Glorification of St. Cecilia (detail, ca. 1727)

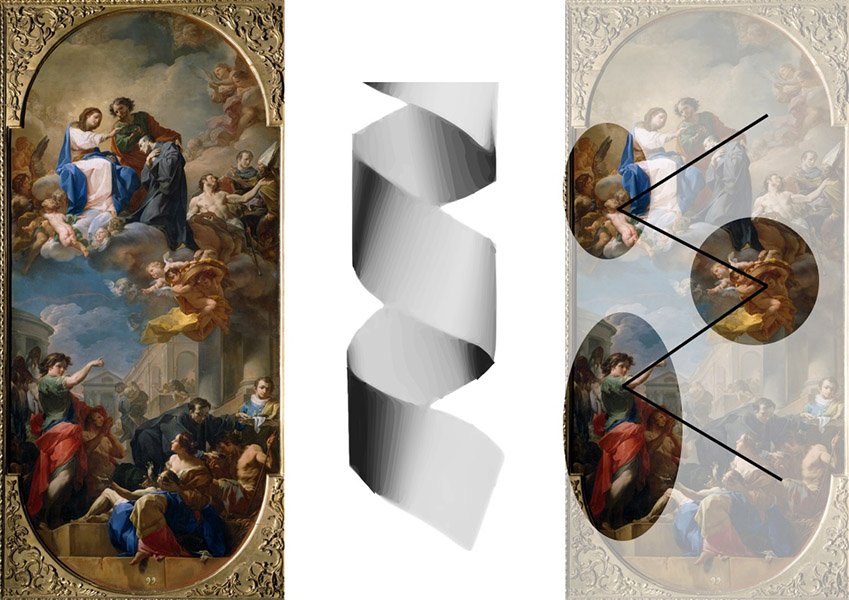

Completing the Geometric Layout

Finally, angels can help to complete a painting’s geometric layout. We won’t go into detail on the art theory here, but suffice to say that paintings usually have a certain geometrical structure that is related to the message they are trying to convey. Here are a few examples of those geometries.

Pyramid

Monumentalism

Stability

Grandeur

Circle

Harmony

Fluidity

Wholeness

Fibonacci Spiral

Organic motion

Natural beauty

Ordered growth

Helix

Ascent

Descent

Change

Chiasm

Balance

Dignity

Central focus

Blast

Chaos

Instability

Drama

Because they are not bound by earthly limitations, angels can act as a flexible visual motif for rounding out the structure of a composition. For example, the Fibonacci spiral that serves as the basis for the painting of St. Januarius below relies critically for its effect on the crowd of cherubs in the celestial register.

Jusepe de Ribera, St. Januarius Emerges Unscathed from the Furnace (1646)

Here is another type of spiral, again composed largely of angels, that funnels the viewer’s attention to the Holy Spirit acting in the scene.

Simon Vouet, Annunciation (ca. 1645)

The angels in this Visitation painting are essential to the triangle-within-a-circle design, representing the harmony between the cousins as well as the monumental significance of the event.

Francesco de Mura, Visitation (ca. 1750)

Finally, Corrado Giaquinto’s Triumph of St. John of God features a helical composition, and note that, each time the arms of the helix change direction, an angel is there to redirect the eye.

Corrado Giaquinto, Triumph of St. John of God (1740)

Bonus: Fallen Angels

During the Q&A session following the original presentation of this material at St. Anselm parish, an attendee drew attention to the fact that the talk focused entirely on good angels. A full-length article could be written on the topic of Demons in Art (a future blog post, perhaps?), but, as a belated response to the question, I’d like to summarize a few key points here.

In the Eastern tradition, fallen angels are often represented as small silhouettes filled in entirely by black. Their general shape (bipedal creatures with shriveled wings) parodies the (good) angels’ beauty, which they once possessed, while their diminutive stature emphasizes their powerlessness to harm people without their consent.

St. Catherine’s Monastery (Sinai), Ladder of Divine Ascent (ca. 1150)

Serbian, Christ Heals the Two Demoniacs (detail, ca. 1350)

A particularly intriguing example of this motif can be seen in the detail of an action-packed crucifixion scene below, where the demon-silhouette is wielding a hooked pole with which he extracts the homuncular soul from the dying body of the wicked thief.

Andreas Pavis, Crucifixion (detail, ca. 1475)

Theologians define evil as the absence of something good (rather than the presence of something bad), and the demons of Eastern iconography, darting across the picture like little black holes of nothingness, visually capture the absence and negation that has come to characterize them.

In Western Medieval art, meanwhile, demons are often represented as a grotesque hodgepodge of animal parts, a portrayal intended to drive home the theological truth that evil is a perversion of the natural order. This approach may also have been inspired by the Book of Revelation, in which earthly powers at odds with God are described as monstrous hybrid beasts, in parody of the noble hybrid beasts (i.e., the cherubim) who serve his throne. The marginalia of the fourteenth-century Taymouth Hours Book provide a representative case-study of this theme.

Taymouth Hours Book, Devils Collecting Souls (ca. 1325)

Another example is this fifteenth-century illumination, in which the demon (in addition to being an incongruous blend of various animal forms) has a second face on his lower abdomen—thinking, as it were, “with his stomach” instead of “with his head.” This motif symbolically associates vice with an excessive focus on gratifying the animal appetites, at the expense of loftier spiritual concerns.

French (Tours) Treatise, Guardian Angel (ca. 1480)

In the Baroque era, meanwhile, many of the attributes of (good) angels are reversed in the portrayal of demons, as exemplified by the Luca Giordano painting below. Whereas St. Michael combines both masculine and feminine qualities, the fallen angels are clearly gendered; whereas St. Michael’s features are idealized and universalized, the fallen angels’ are realistic and particularized; and, whereas St. Michael’s pose is graceful and effortless, the fallen angels are tense and contorted.

Luca Giordano, Fall of the Rebel Angels (ca. 1665)

Demons are often portrayed with reptilian features or body parts, hearkening to descriptions of Satan in Genesis and Revelation. They are also often portrayed with goat-like features, owing to the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats as well as the association of the Biblical scapegoat with sin. A close look reveals that both these elements are at play in the Giordano painting above.

Conclusion

This series of posts on Angels in Art has covered a wide variety of motifs, symbolic language, and artistic devices seen in paintings from throughout Christian art history. Most of the examples we have considered were created hundreds of years ago, but as a sacred artist I can assure you that these principles remain very relevant to artwork being produced today! For an enjoyable challenge to test what you’ve learned, I invite you to go through the GFA Gallery, find the paintings depicting angels that Polly and I have completed to date, and identify instances of the following elements:

Symbolism

Pure intellect/will

Not subject to earthly limitations

Not subject to age/decay

Beatific Vision (music)

Narrative Roles

Adoring God

Escorting into Paradise

Bridging Heaven and earth

Compositional Devices

Introducing signs and symbols

Foreshadowing

Highlighting spiritual significance

Completing geometry.

Can you find examples of all eleven? Have fun!

Further Reading

Giorgi, Rosa. Angels and Demons in Art. Edited by Stefano Zuffi. Translated by Rosanna M. Giammanco Frongia. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2005.

Klimecki, Lawrence. “Saint Hildegard, Fallen Stars, and the Depiction of Evil.” The Way of Beauty. September 21, 2022. <link>

Pope, Hugh. "Angels." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. <link>